There are coastlines. Then there are coastlines. They vary vastly from pole to equator. Some are drowned mountain chains, others hilly escarpments ending in sea stacks, but most I can think of are fairly flat and innocuous. To quote American comic great, Bill Hicks, the place where dirt meets water. These level coastlines are where continental plains slope gracefully, but unspectacularly, into seas and oceans before falling off the edge of the continental shelf and into the inky abyss.

Just once in a while, though, you come upon a coastline which, for all intents and purposes, looks like it was designed by nature to strike undying awe into all humans. Occasionally, that awe extends to – now here i’m thinking bubbly bottlenose dolphins, leisurely leatherback turtles, and even that daft dog you always see barking at the crashing waves – creatures hitherto considered incapable of feeling awed by something abstract like beauty. Its every contour is divinely formed. Its lush, green, & pinnacled backdrop exists to try and upstage the coastline itself, although all it tends to end up doing is to add gloss to the whole picture. Both its outcrops of tide-smoothed megaliths and its oddly-placed vegetation could have been put there by a mythic giant who fancied himself as a bit of a stage designer-cum-cinematographer. Its intertidal waters are so transparent you wonder what the hell’s coming out of the tap.

Its mesmeric surf, unrolling waves onto the shore with all the panache of the footman unrolling the red carpet for his regal passenger, is so impeccably timed as to be the work of some unseen metronome: let’s call him The Earth Philharmonic Conductor. Its sand has been sifted so many times by the daily rhythms that it could pass for castor sugar if it didn’t taste so unlike sugar and so much like, er, minuscule grains of pulverised mollusc. Another defining characteristic of this perfect coastline is that it doesn’t simply disappear into the vanishing point. Rather, it is framed by virtue of being indented in the shape of a half-moon. Its farthest point, as visible by the human eye, is bookended by a mountain of Atlantic Rainforest that slips magnificently into the big blue.

Finally, the whole scene is capped off by a tropical sky, mercifully obscured by a succession of passing clouds that rest briefly in front of a blazing Capricorn sun in order to take the edge off the heat. But failing the presence of a shifting cloudscape, you – the lucky beachgoer – can always cool off racing into the rolling surf, whose temperature is an optimal 22ºC.

The stretch of coast I’m thinking of is one I’ve just returned from. Lying across both an ocean and an equator from the British Isles, tis true it’s far from here. In fact, it follows the Tropic of Capricorn about 43º longitude west of Greenwich, so that places it firmly both in the Western and the Southern Hemisphere. Yes, the sand exudes more heat than the average sole can handle, but there are shady spots, and tables and chairs under leafy fronds, and pretty girls serving chilled caipirinhas and fried morsels of freshly-caught fish. And away in the distance there are old, leathery hippies with beards too long for the sultry air, and joints smouldering away in their mouths. Music drifts in from who knows where. The singer’s language is exotic yet reassuring. Bodies come in all shapes and sizes, but unlike our overdeveloped world obesity is not really a problem. People who come here look after themselves. Elderly whippersnappers bob in the surf, forming a defensive palisade of golden skin and bone against the might of the ocean. I venture that this is pointless, but admire nevertheless their bravery before such a formidable opponent as the Atlantic.

The post meridian on the world’s most perfect length of sandy coast passes in a pleasant reverie. This is the sure sign of a great beach. An even surer sign of skin damage to fair types like yours truly, seeing as the Capricorn sun is now at its apex. The to-ing and fro-ing of the tide complementing the to-ing and fro-ing of my regular forays, from the spot where our parasoled table stands in the granite shadow of a wall of dripping vegetation, down to the world’s clearest water. I sip the dregs of my lime cocktail and watch a boy and a girl on the beach volleying a football between them without it barely touching the ground. She heads, he chests, she volleys it back with the side of her foot. This is impressive stuff. Never let it be said that girls canna kick a ball for toffee.

The day passes both without incident and with plenty of it. In a kind of Schrödinger’s feline paradox, I experience one memorable incident after another without there being the manner of incidents one usually associates with beaches on a hot day: pissed up louts and boors, stealthy gangs of thieves, drowning in the surf, that kind of thing. The first such incidence in my incident-free day starts with an uncanny feeling that i’ve died without a coroner’s report and then gone to heaven without really believing in either God or his long-haired son. It’s a cheat, and can only be got visiting the world’s most breathtaking bit of coastline. It then continues by dipping under the crest of a pulsing sea with my girlfriend’s son, who is beyond delighted to have discovered that such a place as this can really be in this world. The incidents continue with my girlfriend – no swimmer by her own admission – being upended by a wave, screaming in pure terror she hates me, before proceeding to slap me in the face for having brought her not only to a wild coast, but also almost to her untimely demise. I love her even more after that tiff.

What to say other than that was the noblest, most gratifying slap I’ve ever had. And why? Because i found the best bit of coastline anywhere. You could have stripped me of all my worldly belongings, subjected me to summary humiliation, and even proclaimed me dead from cancer within six months, and so long as these awful things were performed there where that sand met that sea, I would forgive practically anyone their everything.

You know you’ve arrived when all along you thought beaches and coasts came a poor second to the mountains inland. Having witnessed this Shangri-La, I’m not so convinced anymore of the inherent superiority of mountains over coasts. It was the best-kept secret outside of Brazil until I shouted my mouth off about it. It’s now the worst-kept. So, here goes….

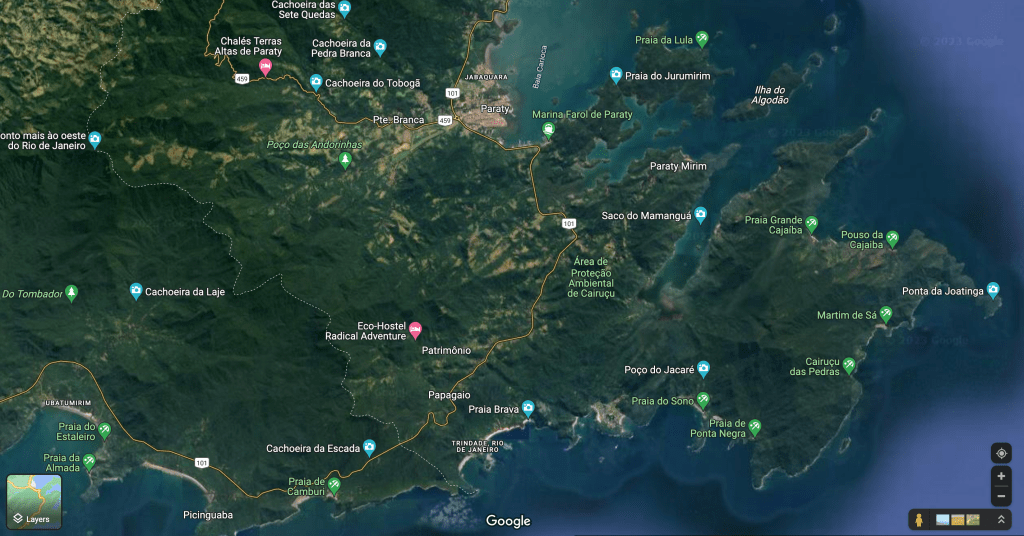

You’re looking, but are you listening? See that little bite out of the green land due south of Paraty? Right on the South Atlantic ocean. The beach is Trindade, just inside of Rio de Janeiro state. Follow Highway 101 from Santos to Rio, and at every twist and turn of what is actually a 4,000km squiggle of bitumen running from Brazil’s south to its north, you’ll be picking your jaw up off the ground. This coastline is the stuff of your wildest dreams. See it before you see your end.